As an investor I could not afford the more ambitious artwork, which went to perceptive syndicates, but I was moved to bid for a cake submitted by one of the many Dave Wilsons who work for the Christchurch Press. It was a light fruitcake, cut and iced to resemble a book open at an inscription about eating one’s own words. Though currently on a diet, I did not hesitate to eat them.

For this is the central mystery of cake art. The cake-eater fulfils the cake-maker, which is why I feel my own edge of ambivalence about Richard Till’s cake, along with Neil Dawson’s entry 4-tier Kiwi house iced epoxy cake, whose ingredients include medium-density closed cell PVC, pigment paste and epoxy resin. ‘Contact with resin can cause blocking of the pores and drowning in body fluids,’ we are warned in the recipe. My instinct suggests that this may be extending cake boundaries too far, reducing the cake to an intellectual toy of the cerebral cortex, rather than a creation which is fulfilling to the crocodile brain as well. Cake art does not lie in holding the cake-as-object at a single point in time, but in an uncompromising progressive relationship in which the observer metamorphoses into consumer, and the cake from outside object to a contained form. Cake is subjected to a series of critical processes, unconscious, yet more stringent and terminal, more organic and subliminal, than any other work of art. The art objet becomes part of the art-lover’s flesh and blood. Its brooding, internalised presence can be apprehended when the art lover steps onto the scales on the day following the consummation.

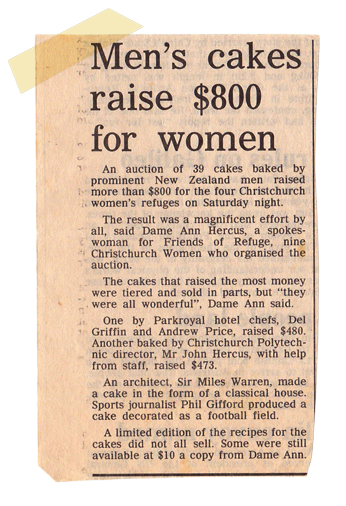

On the days immediately following “The Cake Stall” exhibition, the occasion branched out all over the murmuring city in a series of cake-tasting parties, which kept the flow of cake assessment moving through the community, and because of this I can personally attest to the artistic integrity of John Coley’s No Fail Pomo Chocolate Cake. Cake consumers and cake makers had been united in feeling themselves to be at the advance guard of an art, old in domestic history but needing a new dialectic to express its power and ambience. All praise to Countdown and the Christchurch Polytech who sponsored this remarkable event. Recipe books (in which one may encounter Tom Scott’s Granny Smith Surprise, a word cake which requires the cook to consume at least four gin and tonics) are available, and worth buying, for here one is made aware that cakes have the capacity to become part of literature – but that is another story – and one which slices beautifully.

Originally published in The Listener January 1993, republished in Dissolving Ghosts, Essays and More, Margaret Mahy VUP 2000, and here as a transmedia article with kind permission of Mayhem Multimedia .

Above: Editor of the Christchurch Press,

David Wilson’s “Eat Your Words” cake

Vivienne Stone & Cam Emmerton,

with Lisa Reihana patiently awaiting, cutting John Coley’s

“No Fail Pomo Chocolate Cake”

The Caker, by Jordan Rondel (Random House 2013): a sample of Branded Content Sponsorship in transmedia content.